By Sean Fagan

The gist of this post it to present tracking as the multi-faceted activity that it is. Tracking is very much about engaging your senses and mind with all the minutiae of sign left by living things. It’s often challenging and fascinating.

Oddly, the majority of tracking books are mostly devoted to the tracks and sign of wild mammals and some bird species. But what about amphibians, reptiles, even fish? What about the vast array of invertebrates (of which insects are only a part of the huge number of invertebrates inhabiting earth).

There is so much to see and investigate – so many meanings to tease out.

A common misconception about tracking is that trackers are always striving to seek one of the holy grails of tracking – a super clear print of the foot, preferably a thread of foot prints leading to the actual animal they are tracking. This level of tracking is rare, and highly skillful.

I think a lot of us are familiar with the often stunning documentaries depicting the San Bushmen of southern Africa tracking wild game such as antelopes. Often, they track their quarry until they get a kill. This level of tracking is not only very skillful but generally outside the scope of the casual, or even more serious, tracker.

But tracking (even if our life doesn’t depend on it) is a tremendously enriching, calming and immersive way of engaging with nature...

When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world."

John Muir

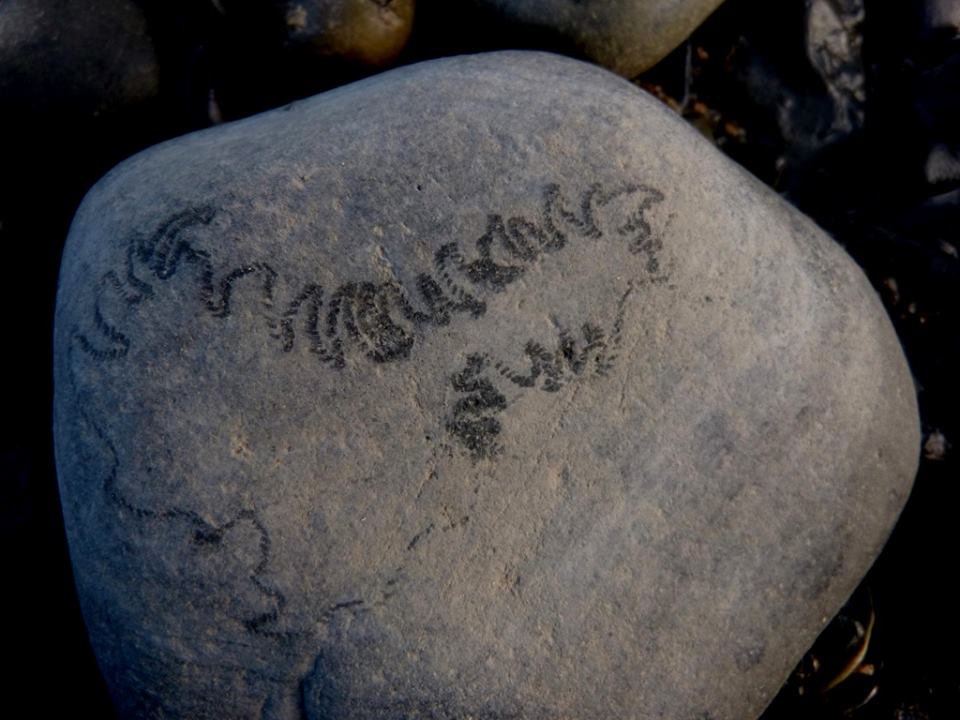

What tracks are these? They are made from a material that is believed to be the strongest biological material tested (more here).

It's the tongue scrapings of a limpet (a coastal mollusc). Limpets have a long tongue with many rows of minuscule, incredibly hard teeth - which they use to scrap off algae from rocks (often scraping off tiny fragments of rock in the process...no wonder they have been referred to as the "Bulldozers of the seashore").

The value of examining animal droppings.

Tracking is not always pretty but with the right mind-set it’s nearly always fascinating...

In above photo - a badger latrine, with many droppings containing, almost exclusively, snail shells.

Highlighting the fact that badgers will opportunistically feed on what's locally available, abundant and easily obtainable (and nutritious).

A common misconception about predation in general is that predators are all striving to take down large-sized prey when in fact many predators will frequently feed upon on small-sized, easily obtainable prey.

In above photo, the bed of an Iberian hare, Lepus granatensis. I often find the beds of wild animals. They are fascinating. In this hare bed - the wide end of bed is where the large hind legs rest while the narrow end is where the head and smaller forelegs rest. Often, when hares (or other mammal species) are resting they will orient their heads towards the wind so as to detect, as soon as possible, the approach of potential predators (Photo: Sean Fagan, Portugal).

Domestic cat tracks - note 4 claw-less toes, large heel pad and overall circular shape (claws are retracted).

Note also the asymmetry of the heel pad and toes - meaning the toes are offset slightly from heel pad - they are aligned at a slight angle away from each other.

Whether you are tracking a leopard, an ocelot or a domestic cat – the key features of cat tracks described above will always be roughly the same – with the most significant difference being the overall size of the different cat tracks (e.g. leopard tracks will obviously be much larger than domestic cat tracks).

That’s one of the great beauties of tracking – once you get familiar with certain tracks you can transfer that tracking knowledge further afield and recognise the tracks of related species. There is a definite commonality of track features between related species.

Something to watch out for.

What's this bird? Note absence of rear toe (indicating it's not a perching bird - a passerine).

Bird tracks that lack a rear toe or have very short rear toes mostly fall into two categories - waders and the unfortunately named - game birds (pheasants, partridges etc.).

Game birds have thick, strong toes whereas waders have slender toes (as in above photo).

The track in photo was found inland in Ireland, and not many wader species frequent inland areas (waders are mostly coastal).

Any guesses? My guess is woodcock or snipe - two relatively common, inland terrestrial waders of Ireland. A third, less probable guess is common sandpiper but that bird species is usually associated with moving water such as rivers.

Can you see how good tracking is a blend of intuitive deduction and hard facts? The hard facts are often gleaned from the study of good tracking books while the intuitive understanding of tracks and sign is garnered from hours of tracking.

Something I don't often find - an enclosed bird-roost site, this one seems to be periodically occupied by a small, solitary bird (judging by the large quantity of small, different-aged bird droppings & the small size of the tree hollow).

During bouts of bad weather some small bird species seek sheltered sites to rest during bad weather.

This roost is a wren roost as I saw a wren leaving this roost when I approached. I've found quite a few of these types of roosts belonging to wrens, Troglodytes troglodytes.

It makes a certain sense - as small animals, like wrens, are more prone to the chilling effects of cold, damp weather - and can easily slip into hypothermia.

In Ireland, the wren is our third smallest species of bird (after the goldcrest & closely related, firecrest).

Tracking Tip: Get to know the paws of your pets

In photo, the underside of a cat paw.

It’s surprising what you can learn when studying the details of an animal’s foot.

Such study can deepen your understanding of tracks - give you a better 'feel' for tracks..

Conclusion

So there you have it - a collection of tracks and sign I came across over the years.

As you can see tracking is much more than finding pristine prints on easy-to-read surfaces such as mud, sand or snow...

It's about searching for all tracks AND sign - sign such as droppings, feeding sign, beds, burrows, old nests, spider webs, earwig eggs...you name it.

It's very much an attitude. At least for myself it is.

Through tracking, we can find coyote fortresses, learn the language of the forest, and become intimate with an animal’s life

Paul Rezendes

Related posts on this website:

Recent Comments